Questions Answered for David and His Family

Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome diagnosis puts things into focus for multiple generations

Sometimes, a genetic condition becomes such an understood part of a family’s story that it can easily be overlooked. Like a good mystery novel, the clues are there from the beginning. But it takes a breakthrough moment for them to reveal themselves.

Such was the case with David, now a 13-year-old from Calvert County, Md. When David was born, his mother Christina remembered, he would bruise easily. Pediatricians attributed it to the young boy learning how to crawl and walk, an explanation that made sense to his parents. But when he returned for his one-year checkup, his doctors were alarmed at the petechiae – pinpoint, round spots on the skin that are caused by bleeding and often look like a rash – forming all over his body.

This time, the doctors were proactive. They ran tests and found that his platelet level was extremely low. Platelets are the cells that help your blood clot, and too few can be a sign of cancer, infection, or other serious issues.

At the time, David’s family was living in New Jersey, and his doctors referred him to the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), where further testing was done on the young boy. But now, Christina was on alert.

“Growing up, my brothers also had low platelets,” she explained. “Those were just words we said back then. It didn’t mean anything.” Christina’s brothers had grown up to lead normal lives, starting their careers and families by the time David was born. While their platelet deficiency was known, it had done little to change their quality of life and had been left untreated for decades.

A few months later, after many tests, David received the diagnosis of Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome, a rare genetic disorder of the immune system characterized by abnormal immune function and a reduced ability to form blood clots. It primarily affects boys. The cure, as the doctors at CHOP informed Christina, was a bone marrow transplant.

Doctors at CHOP immediately set about preparing the 18-month-old boy for the transplant, running tests to see if anyone in his family was a match. Speaking now to the transplant doctors instead of hematologists or immunologists, David’s parents were alarmed at their references to “survival rates.” So, Christina began seeking a second opinion, knowing how typical her brothers’ lives had been. But not just any opinion would do.

“Dr. Wiskott and Dr. Aldrich weren’t alive anymore, but I needed to speak to somebody who [focused their professional expertise on Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome].” Soon, she learned that such a doctor was working at the National Institutes of Health, so she began cold calling associated numbers. Eventually, she got in touch with someone who knew Dr. Fabio Candotti from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). Within a month, the family was checking into The Children’s Inn at NIH for the first time.

“When David was diagnosed, all the other men in my family finally got a name for what they had as well,” Christina explained. “At the time, my brother was 30 years old and had a family. My other brother was in his 20s. I had uncles and great-uncles and things like that. So, we thought that maybe we’d just live with it.”

Indeed, Dr. Candotti pinned David’s case of Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome at a two on a scale of 1-5. At his recommendation, David began undergoing immunoglobulin infusions to manage his condition.

“We lived with it for a long time,” said Christina. “But it was always with the knowledge that it could get worse. He never really had a compromised immune system. His body never did what the numbers said it should. His platelets were low, but he never had any serious active bleeding.”

David took some basic precautions as he grew up. Contact sports were out, even though he loved watching football and baseball. Instead, he took up swimming and riding dirt bikes. He was also a tinkerer, and he set about teaching himself how the world worked.

“He has an engineer’s brain,” Christina smiled. “Even from a very young age, he would take apart pens to figure out how they go back together.”

Having connected with Dr. Candotti, David and his parents began regular visits to NIH and The Inn. “They used to have a really cool treehouse in the playroom,” he remembered. He also recalled the wooden bird’s nest that used to be in the playground as a highlight during his early visits.

The immunoglobulin infusions became a part of David’s routine, getting injected multiple times a week, including subcutaneous injections once a month. The grind took its toll, and David showed no signs of a weakening immune system. Doctors even admitted that they were unsure that the treatments – which left David’s body little time to recover from the constant injections – were essential. So, last year, he made a decision. “I didn’t want to do the therapy anymore,” he explained. “I’d have to get two needles in my stomach every week.”

Shortly after voluntarily stopping the treatments, David got a nasty infection. The question of whether the treatments had been necessary was answered. Still, doctors encouraged him and his parents to view the setback as a blessing in disguise.

“Now they knew he was going to need a bone marrow transplant,” Christina said, “But it could be planned. It wasn’t urgent. It would have to happen, but we could plan to fit it into our lives. David is in the eighth grade now and could go back to school by the end of the year. Then they will all go off to ninth grade, and everybody will be new to everybody.”

David, Christina, and his father, Dave—who had just retired from the United States Navy as a Master Chief—arrived back at The Inn in June 2023, where they underwent testing for two weeks. David recalls the eye tests as being the hardest. Fortunately, he had several matches for his transplant, a luxury that allowed doctors to dig deeper into the genetic makeup of the matches to ensure the best possible option. Eventually, they settled on a 38-year-old male American donor.

David cooking at The Inn

The transplant went smoothly. As he recovered, there was one hiccup – almost literally. Shortly after the procedure, he developed a cough and was intubated for a test. As doctors brought him out of the intubation, David got a coughing fit so severe that it damaged his throat, and he had to be re-intubated and sedated in the Intensive Care Unit for nine days as his throat recovered. After that, though, David was back at The Inn just 39 days after the transplant.

The Inn, Christina explained, was always a welcoming environment full of people – families and staff – whose kindness and encouragement buoyed her family. But as they rarely made visits longer than a week in the years after David’s diagnosis, they were discovering new Inn amenities even now after more than a decade.

“I never really understood why they gave us our own fridge and things like that,” Christina laughed. “We would come for a few days or maybe just an overnight. But now, The Inn has been a godsend. After being in the hospital for so long, the food gets old. But we had our room at The Inn, so I could come down and get us something to eat or get our stuff while he was still in the hospital. And medically, I had to take care of [David], but I had two other kids who needed to feel a part of this and needed to have mom and dad as well. The Inn let that happen. They would come and stay, and my husband would go and stay with him sometimes, or we would swap it out. It’s very trying on a family, so offering a way to try to keep us connected was a godsend.”

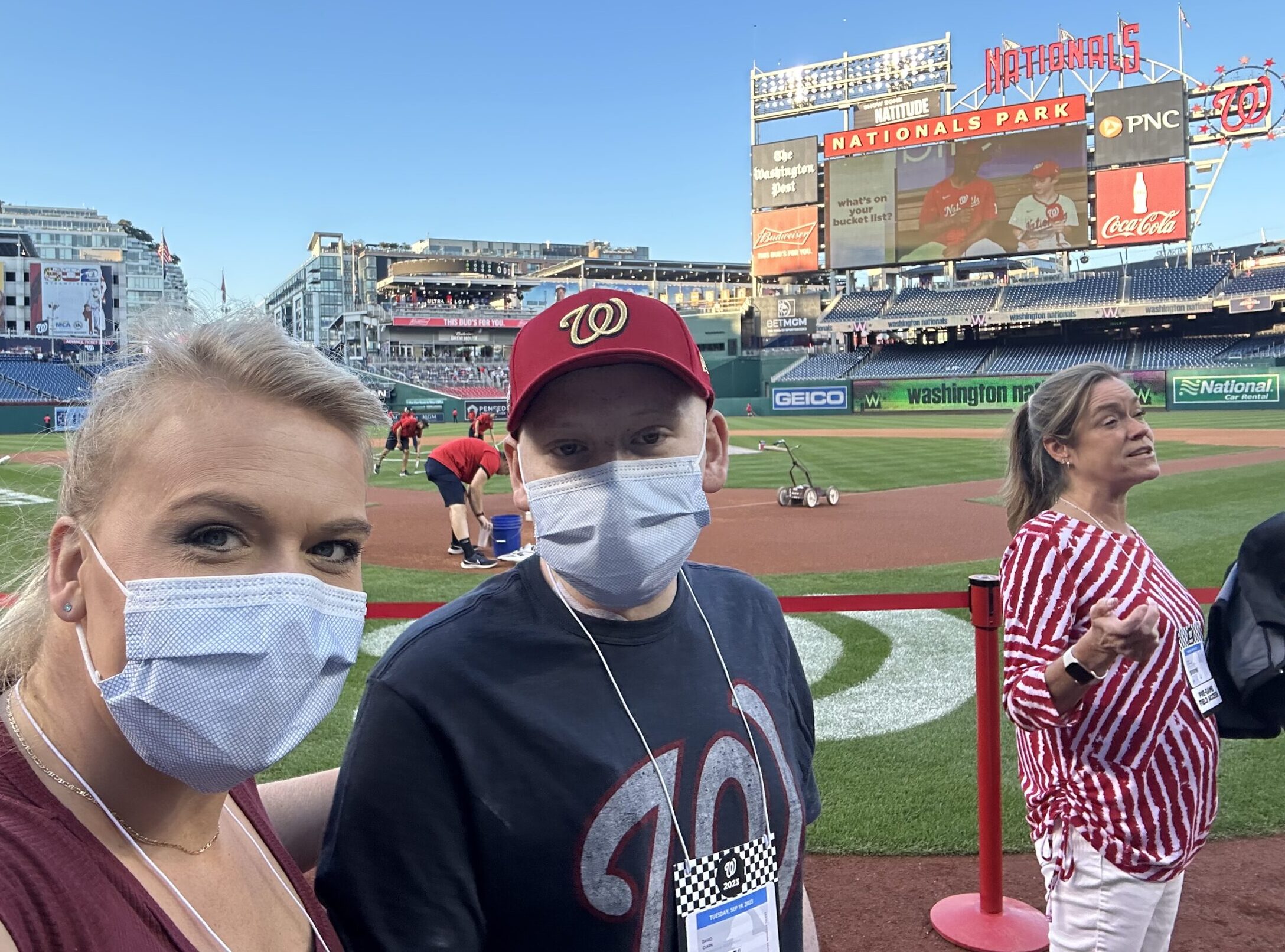

Remaining at The Inn for further observations in the months following his transplant, David has particularly enjoyed the many sports-related programs that The Inn has put on. He especially singled out the unique opportunity to throw out the first pitch at a Washington Nationals game last September. It was his second Major League game, after a Padres game while his father was stationed in California.

David also talked football with members of the Washington Commanders when they came to The Inn in late October. With Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome now behind him, he hopes to join the football team when he begins high school in the fall. His most significant obstacle to that may not be his health but his mother’s blessing. Even she admits, though, that he is “built like a linebacker.”

David’s journey has taken him from infancy to the brink of high school and has, at times, been a difficult and grueling one. But it has provided answers for his family. Now, rooted in Southern Maryland after a lifetime moving across the country, he is ready to tackle what comes next, whatever that might be.