Three Birthdays and One Extra for Good Luck: Everett’s Story

Little Everett Schmitt celebrated his 3rd birthday on May 29th this year during his first trip to the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Nurses brought balloons, cards and a big chocolate cake.

Four months later, on September 15, at the NIH Clinical Center, his family marked an honorary birthday – ‘Day 0’- when he received long-awaited gene therapy treatment. The gene therapy consisted of an intravenous infusion of his own previously collected blood-forming cells. These cells had been corrected while growing for 3 days in a laboratory culture.

Day 0 was a day filled with hope and expectation that this innovative treatment would signal the start of a chance at a healthy life for the effervescent, yet seriously ill toddler.

After the party, “He asked if he was turning 4,” says his mother, Anne Klein. “We explained that this was a new birthday, to celebrate the day he starts to get healthy.” His father, Brian Schmitt brought cards from his big brother Alden, 5, who is back home in California with his grandparents. Friends and family sent photos showing support by lighting a candle for Everett, which Anne plans to compile into an album for Everett.

Everett is battling severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), a group of rare, life-threatening genetic disorders in which white blood cells that normally fight infections don’t function properly. Without a working immune system, SCID patients are susceptible to recurrent illnesses, such as pneumonia, meningitis and chicken pox. The condition is fatal, often within the first year of life, unless affected infants receive immune-restoring treatments, such as bone marrow transplantation.

Everett was diagnosed at birth through newborn screening with X-linked SCID, which means he inherited the genes from the X-chromosome, passed on by his mother. His mother donated bone marrow for his transplant when he was just seven weeks old. While life-saving, this type of transplant only partially restores immunity and most often fails to restore the ability to make antibodies, says Everett’s physician, Dr. Harry Malech, Chief of the Laboratory of Host Defenses, at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). Antibodies play an important role in the immune system. They circulate in the blood and other body fluids, defending against invading bacteria and viruses. Since Everett’s transplant in infancy did not completely restore his immune system, he continued to suffer from recurrent infections and also has required monthly injections of antibodies. He has lived in isolation for most of his life, bonding closely with his big brother.

At the NIH, he is enrolled in a NIAID gene therapy clinical study. Anne still remembers how Everett’s face lit up when he first walked through the front doors of The Inn. He caught site of the expansive playground, and ran to check it out. Both boys revel in The Inn’s two tree houses, one outside and one inside on the second floor. The Inn’s slides and swings have been a great escape, Anne says.

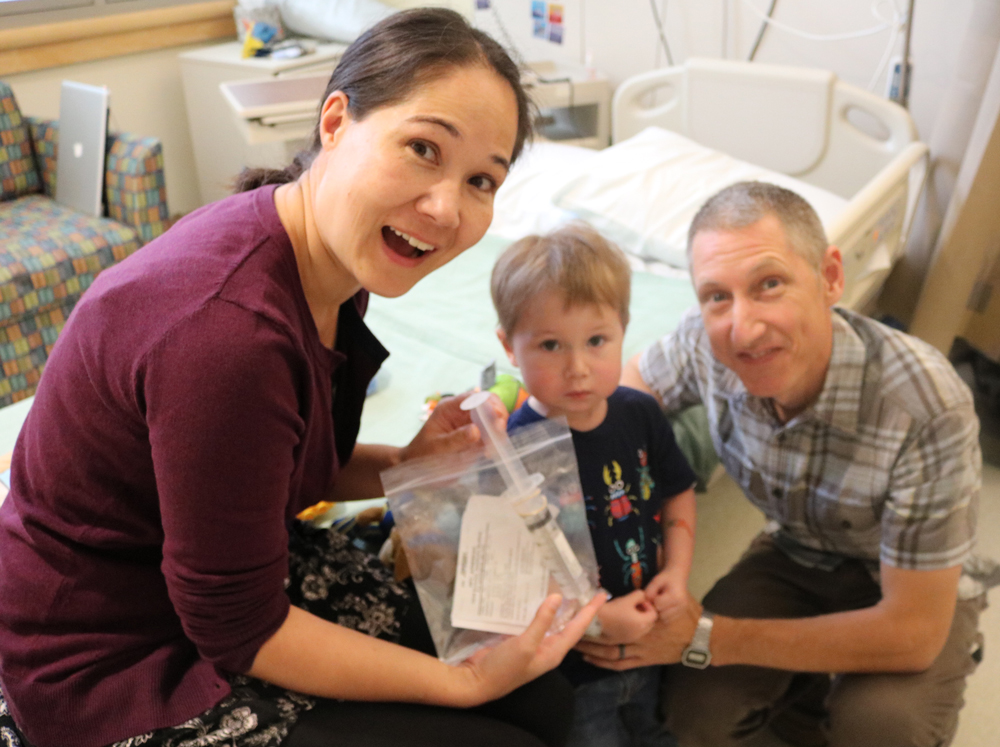

A week after the Big ‘Day 0,’ treatment, Dr. Malech stopped by Everett’s hospital room to give his mom an update. The procedure involves injecting millions of Everett’s own stem cells with a corrected gene in the hopes that his body will begin to build a healthy, functioning immune system. Anne recalled that Everett’s first bone marrow transplant that used her cells shortly after his birth resulted in severe complications.

“My cells have caused a lot of problems,” Anne says. Dr. Malech quickly reassured her, saying that many of the initial bone marrow transplants are problematic, but “Your cells saved his life.”

Anne and Brian named Everett after an old English word, meaning brave as a wild boar. In his short life, he certainly has lived up to his name. During this 5-6 week hospitalization for the gene therapy treatment at the NIH, Anne and Everett are separated from the rest of the family. Anne is missing Alden’s first months of kindergarten. The family enjoyed an impromptu reunion during the first weekend in October, when a local Maryland charity, L-Dub’s Love, headed by parents who lost their daughter to cancer at the NIH, paid for Brian and Alden to fly to Maryland and surprise Everett.

Brian and Alden both found suitable hiding places in Everett’s hospital room. Brian climbed in the closet, which Everett has renamed his “house,” because he pretends to go through the door and head home. His mom told him that he should show the nurse his “house,” and when he rushed to the closet, he jumped with excitement when saw his dad. “Now he really thinks the closet is his house,” Anne says.

Then, his mom and dad suggested Everett check his “secret hiding spot,” a small wedge behind the chair that Everett and Anne had draped with a sheet to form a makeshift tent. As Everett turned to the chair, he spotted Alden and the two jumped to hug one another. They’ve been playing non-stop. Alden renamed Everett’s bed a space-ship where they launch many trips.

The visit also coincided with better results from Everett’s cell counts, Anne says. Ultimately, the treatment goal is to sufficiently restore Everett’s immunity so that repeated long hospitalizations will be only a memory.

As Anne writes on her blog, keeping family and friends informed, there is a bright side: “It’s so much better being in the hospital for a promising treatment than for one of Everett’s traumatic health events. We are feeling optimistic that this trial will allow Everett and our family to experience a better quality of life when we come out on the other side.”